The lecture is a long-standing method of instruction that, while appropriate to some learning situations, is not ideal in others. On this page you will find information about the strengths and weaknesses of lecturing, as well as active learning techniques that you can easily use to engage students during a lecture. For more detailed information on active learning strategies, models, and research, consult our companion bibliography Resources on Active Learning.

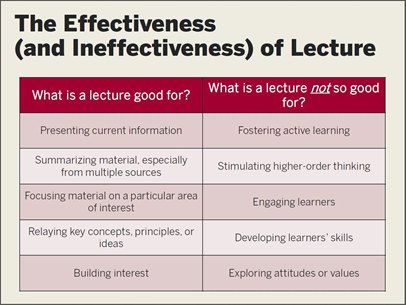

Lectures are good for:

- Presenting current information

- Lecturing is a great way to fill the gap between current research and what’s already published.

- Summarizing material (especially if you are drawing on multiple sources):

- A summary lecture is not an attempt to water-down course content. Instead, the goal should be to provide a lens through which students can understand the greater whole.

- Focusing material on a particular area of interest:

- A good lecture should indicate how course content fits, here and now, with the background and interests of your particular group of students.

- Relaying key concepts, principles, or ideas:

- This approach helps learners identify what matters and what is less important. These sorts of lectures can be short and simply review the key points to give form and context to a student discussion or activity.

- Building interest:

- If (and only if) a speaker or teacher is highly passionate about a topic that is relatively new to an audience, then a lecture can be a great way to spark the interest of and motivate that audience. For example, think about a good keynote or introductory presentation you’ve seen at a conference.

Lectures are not good for:

- Fostering active learning: Active learning gives students the opportunity to engage with and respond to the course material. The emphasis is on developing students’ skills rather than on information transfer. Active learning techniques can be added to traditional lectures (see below). Since lectures do not stimulate active learning, they do not help with the following traits of active learning:

- Simulating higher-order thinking

- Engaging learners

- Developing learners’ skills

- Exploring student attitudes or values

Tips for Making Your Lectures More Active:

Ask Students What They Know or Think about Class Content

- Background Knowledge Probe. Administer a short, simple questionnaire at the beginning of a course, at the start of a new unit or lesson, or prior to introducing an important new topic. For students, it highlights key information to be studied, offering a preview of material to come and/or a review of prior knowledge. For instructors, it helps determine the best starting point and the most appropriate level for a lesson.

- Classroom Opinion Poll. Use clickers or signs to have students give their opinions on an issue or question.

- Focused listing. This activity helps determine what learners recall about a specific topic, including concepts they associate with a central point. It can be used before, during or after a lesson. Students write key word at the top of a page. For 2 – 3 minutes, they jot down related terms important to the understanding of that topic. They then pair up with peer, sharing lists and explanations of why concepts were included. This will build their knowledge base and clarify their understanding of the topic.

Learn about Your Students

- Interest/Knowledge/Skills Checklists. Create checklists of topics covered in your course and skills strengthened by or required for succeeding in those courses. Students rate their interest in the various topics, and assess their levels of skill or knowledge in those topics, by indicating the appropriate responses on the checklist.

- Goal Ranking and Matching. Ask students to list a few learning goals they hope to achieve through the course and to rank the relative importance of those goals. If time and interest allow, students can also estimate the relative difficulty of achieving their learning goals. The instructor then collects student lists and matches them against his or her own course goals.

- Course Related Self-Confidence Survey. Individuals who are generally self-confident may lack confidence in their abilities or skills in a specific context – for example, in their quantitative skills or their ability to speak in public. Use a survey to get a rough measure of students’ self-confidence in relation to a specific skill or ability.

- Self-Assessment of Ways They Learn. Ask students to describe their general approaches to learning by comparing themselves with several different profiles and choosing those that most closely resemble them. Because there are a number of ways to describe ways of learning, faculty choose their own sets of profiles to use in assessing students.

Prompt Students to Talk About Course Content with Other Students

- Think-Pair-Share. Pose a question, allow students to jot their responses. Then students pair up and share what they wrote. A whole group discussion can follow.

- Active Knowledge Sharing. Provide a list of questions pertaining to the subject matter you will be teaching. Ask students to answer the questions as well as they can. Then invite them to mill around the room, finding others who can answer questions they do not know how to answer. Encourage students to help each other.

Provide Organizational Prompts

- Empty Outline. Provide students with an empty or partially completed outline of an in-class presentation or homework assignment and give them a limited amount of time to fill in the blank spaces.

- P-M-I. Prepare a table with three columns, with the headings “Plusses,” “Minuses,” and “Interesting Points.” Students use the table to critique a particular topic, concept, or idea.

- Categorizing Grid. Students are presented with a grid containing two or three important categories, superordinate concepts they have been studying, along with a scrambled list of subordinate terms, images, equations, or other items that belong in one or another of those categories. Learners are then given a very limited time to sort the subordinate terms into the correct categories on the grid.

- Memory Matrix. This is a two-dimensional diagram, a rectangle divided into rows and columns used to organize information and illustrate relationships. In a Memory Matrix, the row and column headings are given, but the cells are left empty. When students fill in the blank cells of the Memory Matrix, they provide feedback that can be quickly scanned and easily analyzed.

- Pro and Con Grid. Ask students to jot down quick lists of pros and cons related to a topic.

- Defining Features Matrix. This requires students to categorize concepts according to the presence (+) or absence (-) of important defining features, thereby providing data on their analytic reading and thinking skills.

Have Students Apply or Restate Content

- Applications Cards. After students have read or heard about an important principle, generalization, theory, or procedure, hand out an index card and ask students to write down at least one possible, real-world application for what they have just learned.

- Directed Paraphrasing. Ask students to paraphrase part of a lesson for a specific audience and purpose, using their own words.

- One Sentence Summaries. At the end of the discussion, have students summarize the overall concepts in a one-sentence format: Who did what to/for whom, when, where, how, and why?

Find out What Students are Learning

- Minute Paper. The most common format asks students to recall and self-assess their understanding. Ask a question like “What was the most important thing you learned today?”

- Muddiest Point. A variation of the minute paper, asking for feedback about where students are still confused. Ask a question such as “What questions remain uppermost in your mind as we conclude this class session?”

The Top Ten Guidelines for Lecturing

- Remember that lecturing is not well suited for higher levels of learning.

- Decide what you want the students to know and be able to do as a result of the lecture.

- Outline your lecture and share that outline with students.

- Choose relevant, concrete examples.

- Find out about the students, their backgrounds, and their goals.

- Permit students to stop you to ask questions, make comments, or ask for review.

- Intersperse periodic summaries.

- Start with a question, problem, or current event.

- Watch the students. If you think they don’t understand you, stop and ask them questions.

- Use active learning techniques.

References

Angelo, T.A. & Cross, P.K. (1993). Classroom assessment techniques: A handbook for college teachers. (2nd ed.). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Bligh, D.A. (2000). What's the use of lectures? San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Clark, D. (2010). Bloom’s taxonomy of learning domains.

Cashin, W.E. (2010). Effective lecturing. Idea Paper #46

Davis, B. G. (2009). Tools for teaching. 2nd. Ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Dubbin, R. & Taveggia, T.C. (1968). The teaching - learning paradox: a comparative analysis of college teaching methods. Center for the Advanced Study of Educational Administration.

Heppner, F.H. (2007). Teaching the large college class: A guidebook for instructors with multitudes. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

MacGregor, J. (2000). Strategies for energizing large classes: From small groups to learning communities. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

McKeachie, W.J., et al. (1987). Teaching and learning in the college classroom. A review of the research literature. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan.

Schonwetter, D. J. (1993). Attributes of effective lecturing in the college classroom. Canadian Journal of Higher Education, 23 (2), 1-18.

Silberman, M. L. (1996). Active learning: 101 strategies to teach any subject. Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Smith, K., et al. (2005). Pedagogies of engagement: Classroom-based practices. Journalof Engineering Education, 94 (1), 87-101.

Revised by James Gregory (January, 2016)

Revised by Terri Tarr (October, 2011)

Authored by Peg Weissinger (February, 2003)

Recommended Books

Subject: EDUCATIONAL EVALUATION; EDUCATION / Evaluation & Assessment

Subtitle: A Handbook for College Teachers

UPC: 9 7815554250 5

Subtitle: 101 Strategies to Teach Any Subject